Discovery

DISCOVERY IN A NUTSHELL

The first phase of our service design projects requires us to familiarize ourselves with the users, providers, and stakeholders of the service we are designing. Integral to this initial phase is identifying challenges and opportunities surrounding the service context and understanding the value that the service is intended to deliver. Getting to know problems and possibilities of everybody involved necessitates a variety of research methods. While this stage is often referred to as "design research," we prefer calling it "discovery" which emphasizes the sometimes accidental nature of knowledge production and sense-making. What we discover can range from mundane insights to complex connections only visible to those who are deeply embedded in the context for which we design.

Drawing from methodological insights of the social sciences, we conduct interviews, observe people’s interactions, and do literature reviews. Although our starting point is an exploration of specific interactions, experiences, and relationships in order to inspire ideas for innovating on a particular service, our findings may have larger social or policy implications. During the discovery phase, we expect to find and negotiate differing perspectives and conflicting interests, generate empathy and understanding among stakeholders, and promote engagement with the design process going forward.

OUR STARTING POINT

Given the limitations and possibilities presented by the EITC, any project that takes as its objects the delivery of free tax services has to take into account the effects of an anti-poverty program such as the EITC. Families earning a yearly income below 40 per annum receive a tax credit after they filed their yearly return. This one-time payment is affected by dependent children and the amount earned by every family and goes up with every dollar earned until it plateaus. That means that until a certain point those families who earn more also receive more credit, an incentive to become or remain employed and therefore off the welfare roles. Nonetheless, families making below 40k a year often find it difficult to save up as research shows, and thus rely on the yearly credit to finance education or other assets. While in theory this may appear functional, in practice the economic efficacy enabled by the EITC is impacted by an industry that has evolved around the growth of this tax credit program. Such private tax services often charge so much that a significant amount of the potential credit has to be spent on tax preparation. In contrast to for-profit companies targeting specifically EITC recipients, free tax services are are inefficient or simply not user-friendly and as a result do not satisfy the needs of many low-income tax filers

WHAT WE DID

In Tax Time Services the general discovery process was influenced by specificities of the social context. Before tackling the political and economic problems of taxes for low-income New Yorkers, we needed to start our process on the basis of theoretical background research informing ourselves about the EITC, VITA, and other financial programs. In order to deal with the complexities of emerging problems, we had to assemble a team of designers, policy advisors, and public sector workers that could handle the complexities we would encounter along the way.

Our collaboration with the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs Office of Financial Empowerment and The Food Bank for NYC exposed us to an existing pro-bono tax service, Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA). While originally established by the IRS in 1969 to serve the needs of low to moderate income families, the elderly and disabled, and persons with limited English proficiency, this service is provided to through partnerships with private organizations, community volunteer organizations, universities, or non-profits. In New York, this service is supplied by The Food Bank for NYC. In a system of growing income inequality it represents an important factor that addresses the need to receive tax refunds for low-income communities. Within our research process, we held forums and panels in which Food Bank employees shared their experience with VITA services. As a result, we were able to draw from the everyday expertise and insights of people involved.

Following theoretical inquiries and broad-scope panels, we conducted interviews with current and potential users of VITA, and observed the intake process on-site. Hearing the opinions of people who were negatively affected by private paid tax preparers gave substance to our aim to expand existing capacities of VITA services. This part of the discovery phase, along with feedback from Food Bank employees, crucially informed the next step of our process and continues to inform prototyping and possible implementation suggestions. Discovering the network of links between the various stakeholders, we began visualizing their connections in a map (link stakeholder diagram) that allowed us to quickly identify points of tension within existing services but also highlighted areas of possibilities, connections and relationships that present possibilities for new services.

We identified a number of tension areas within existing services, which present design opportunities.

- On-location filing processes were congested, leaving people with long wait-times often coupled with frustration of being sent away after hours of waiting due to missing documents.

- Locations are often far away from filer’s homes or difficult to reach alongside family and sometimes multiple job obligations.

- Many filers find a sense of security in seeing their taxes done in front of them, but the virtual process relies on remote processing. Virtual VITA also necessitates phone communication for confirmation of details, but filers can be difficult to reach, especially from unfamiliar phone numbers.

- Filers who choose to travel to designated VITA locations often do not have the necessary information and therefore frequently fail to bring all required documents.

- Not enough members of low-income communities take advantage of these free services or even know about VITA despite flyer distribution and word-of-mouth promotion.

DISCOVERY CONTINUES

Within the discovery phase, we encountered the necessity to pose larger questions to the tax preparation system. This prompted us to define the scope of this project, circumscribe what is possible, but also what is necessary. In an interdisciplinary team, the questions that arose, while sometimes reaching the limits of design precedents, were ultimately geared toward exploring possibilities of our partnership that expanded and redefined the present relationship between public services and their stakeholders. In this process, we also have to collectively ask how we can use the political and social insights gathered from such a project to productively engage communities and possibly also apply this knowledge to other areas of community development. This demonstrates that, as a partnership of different interest groups with a variety of knowledge-bases and fields of expertise, we are able to generate experience not limited to any of our specific disciplines but that bridges some of the existing divides between design, policy, and service provision. Opening up routes for public participation that go beyond research and into jointly utilizing discoveries, we hope to critically and reflectively engage with problems and possibilities of tax services for low-income New Yorkers.

What we used - Tools & Methods

BACKGROUND RESEARCH

Before trying to make any discoveries of our own, we learn all that we can from the work of others. Reviewing surveys, studies, essays, articles, and other literature allows us to build on existing knowledge and direct our efforts toward what remains to be discovered. In addition to this focused secondary research, we often conduct a broader exploration of potentially analogous products or programs that could offer new ways of thinking about services that we are trying to design or change.

SYSTEM DIAGRAMMING

When words aren't enough, we visually depict our ideas. Mapping out service systems and diagramming relationships between stakeholders can help to situate discovery findings in context, align the understanding of collaborators and stakeholders, and illustrate areas of opportunity for innovation. We often find the process of creating these visualizations to be as revealing as the visualizations themselves, so we try to think about them as evolving documents and working theories.

STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS

A significant part of our discovery work is often devoted to conducting interviews with the users, providers, and other stakeholders of a service. Typically, these are semi-structured conversations guided by a flexible set of prepared questions. Instead of asking interviewees about what they want or need, we try to engage them in telling stories about what they feel and do. This allows us to collect actionable insights, test initial theories and assumptions, and foster empathy between our design team and service stakeholders.

CONTEXTUAL OBSERVATION

In addition to simply asking service stakeholders about their experiences, we often seek out opportunities to directly observe them using, providing, or supporting services. This allows us to account for the fact that there's sometimes a difference between what people say they do and what they actually do. In-person observation and on-site "shadowing" also provides us with a visceral sense of the conditions in which a service takes place and helps us understand the design constraints present in this context.

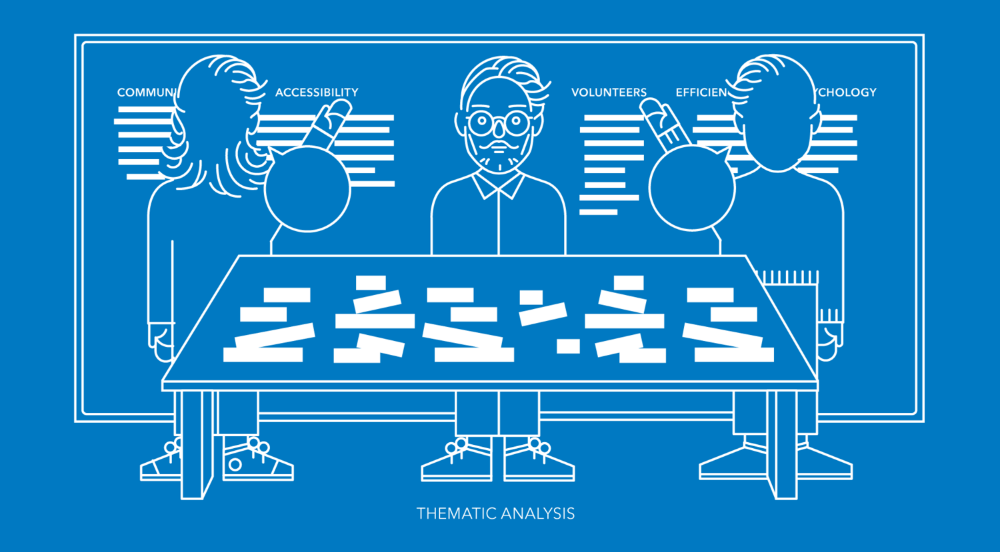

THEMATIC ANALYSIS

Once we have gathered enough insights to give us a sense of the main challenges and opportunities present within a particular service context, we take a moment to stand back and look for patterns or themes emerging from the data. Writing or printing the individual insights on cards or sticky notes and tagging, coding, or categorizing them in different ways allows us to create novel combinations of ideas, reframe our understanding of old design problems, and reveal new solution spaces that we might have otherwise missed.

STAKEHOLDER PERSONAS

In order to communicate our discovery findings to partners and collaborators, and to help maintain a human-centered focus in our design process going forward, we often create fictional but representative characters, or "personas," that embody important qualities of the stakeholders or situations we are designing for. These personas may also play important roles in ideation or scenario-building activities, and they can serve as proxies for stakeholders and advocates for their needs in later decision making and consensus building.

References

Informing Our Intuition - Jane Fulton Suri

Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping - Paco Underhill

Communicating Design Research Knowledge - Lois Frankel

The Agency of Mapping - James Corner

Deconstructing Analysis Techniques - Steve Baty

The Social Design Methods Menu - Lucy Kimbell + Joe Julier

Design Research: Methods and Perspectives - Brenda Laurel

Doing Research In The Real World - David Gray

Tax Time ServiceS Assets

Stakeholder Diagram

A visual representation of our evolving understanding of the stakeholders involved in promoting and providing tax preparation services for low-income New Yorkers.